Scar correction

General information

A scar is an inevitable consequence of skin discontinuity. As a plastic surgeon, I strive to improve the function and form of various areas of the human body, but this is always associated with an unavoidable scar that results from surgical wounds. Skillful creation and manipulation of scars are an integral part of a plastic surgeon's work. Even before starting any operation, I think about the final appearance of the scars. Almost always, my patients ask me about ways to influence the scar to make it as inconspicuous as possible. There is no simple or short answer to this question. It requires extensive discussion. Firstly, if a scar has already formed, it cannot be removed. A scar is a permanent and inevitable consequence of surgery and injury. One can only strive to achieve an ideal scar. An ideal scar has the following characteristics: 1. It is linear; 2. Narrow; 3. Is level with the surrounding tissues (neither raised nor depressed); 4. Pale, and its color resembles the color of the surrounding healthy tissues; 5. Soft and of a similar structure to the surrounding tissues and movable relative to the underlying tissue; 6. It is located along natural physiologically occurring depressions and lines on the human body; 7. It does not cause any discomfort, such as itching, burning, or pain.

The final appearance of a scar depends on many variables, and we only have control over some of them. What variables influence the final appearance of a scar?

Type of wound (surgical wound vs. accidental injury); During surgery, the surgeon creates a surgical wound with a scalpel. This is the smallest possible injury. Operating conditions are sterile. The patient usually receives prophylactic antibiotics to reduce the risk of infectious complications. At the end of the operation, the wound edges are approximated with sutures. The incision line is planned and chosen so that the inevitable scar is as inconspicuous as possible. The opposite of a surgical wound is a traumatic wound. The location of the injury is accidental. The instrument causing the injury is not sterile, and often heavily contaminated. The edges of a traumatic wound are jagged, often crushed, and tissue loss often occurs. A certain period usually passes from the injury to the provision of professional medical help. During this time, bacteria can multiply in the wound, significantly increasing the risk of complications in wound healing. Statistically speaking, a scar at the site of a surgical wound will much more often resemble an ideal scar compared to a scar at the site of a traumatic wound.

Wound location (body area, direction relative to Langer's lines); Different scars form in different areas of the same person's body. Scars resulting from wound healing on the eyelids and external genitalia are most similar to ideal ones. Scars in the deltoid and sternum areas usually have a hypertrophic character. Facial scars located along Langer's lines of reduced tension are usually inconspicuous, while scars on the back always become wide over time. This is due to the tensile forces acting on the healing wound. Where the skin is less tense and lax, scars will be less visible. Where there is high tension at the wound edges, scars will always initially be hypertrophic (raised above the surrounding tissues), and ultimately atrophic (depressed relative to the surrounding tissues). The direction of the wound relative to Langer's lines of reduced skin tension is of great importance for the appearance of the scar. Scars located along Langer's lines are narrow, while those running across them are wide. Knowledge of Langer's lines on the human body allows a plastic surgeon to consciously direct their incisions. In a case where it is necessary to remove a skin lesion located in the deltoid area, even the most excellent plastic surgeon, using the highest quality tools and suture materials, will not achieve an ideal scar at the excision site. He can only inform the patient about this before the procedure, so as not to have to explain it afterwards. Here, the type of scar will be mainly determined by the location of the inflicted wound.

Method of wound healing (per primum vs. secundum); A surgical wound usually heals by so-called primary intention (per primum). This means that at the end of the procedure, the wound edges are approximated with sutures and adhere, forming only a small amount of scar tissue. In the case of healing traumatic wounds with tissue loss or in the case of wound dehiscence, healing proceeds by so-called granulation and epithelialization (per secundum). This means that the defect resulting from injury or dehiscence is first filled by granulation tissue, and only then covered by epidermis from the wound edges. A wound healing by primary intention, whether surgical or after accidental injury, will almost always result in an ideal scar, while a wound healing by granulation will almost always result in a hypertrophic scar.

Patient's age; Healing processes in young people and children are more intense than in older people. Scars in older people quickly become less visible because collagen production processes are less intense. Scars of similar location in children will mature longer and be more visible because healing and collagen production processes are more intense.

Patient's genetic predispositions; Every person is different and unique. This also applies to the intensity of wound healing processes. Scars of the same location in two people of the same age, operated on by the same surgeon, can be completely different. This results from the individual characteristics of a given patient. The tendency to form hypertrophic scars or keloids can be predicted before surgery based on carefully collected medical history and examination of existing scars on the patient's body. Everyone has had vaccinations in the past, so it is worth examining the left arm to assess vaccination scars.

Surgical technique and suture material; Surgical technique during wound closure should be very delicate, and movements very precise. In the medical community, it is said that a surgeon should have the hands of a woman, the eyes of a hawk, and the heart of a lion. In my practice, I often use loupes and microsurgical instruments to increase the precision of my actions. Surgical instruments should be adequate for the wound being sutured. The wound should be sutured in layers – this means that the tension will be distributed over many layers and many sutures, which ultimately translates into scar quality. Every accidental traumatic wound should be converted into a surgical wound. This involves the so-called surgical debridement of the wound. Jagged and uneven wound edges should be excised, the wound cleaned of dead tissues and foreign bodies, and irrigated to remove as many even small contaminants and microorganisms as possible.

Suture removal time; There is a general rule that the longer sutures remain on the edges of a skin wound, the less chance there is of achieving an ideal scar, as additional scars will form across the wound at the suture sites, resulting in a so-called „ladder” rather than a linear scar. To avoid skin sutures placed across the wound, they can sometimes be replaced with an intradermal suture, but this is only possible in some wounds. Sutures are kept for varying lengths of time in different body areas. Sutures can be removed fastest from the eyelids – even after 5 days. They are kept longest, up to 14 days, in areas where the greatest forces act on the wound edges – the back, lower limb. To achieve a compromise, some sutures can be removed earlier, and the rest later. In this way, we care for the appearance of the scar and at the same time protect the wound from dehiscence due to sutures being removed too quickly.

Adherence to postoperative recommendations; A scar undergoes long-term processes of spontaneous maturation and remodeling, and therefore achieves its final appearance no earlier than 1 year after the wound has healed. The most important factor influencing the final appearance of a scar is the passage of time. However, it is worth following certain generally accepted methods of scar care during its maturation period. Until the sutures are removed, the healed wound should be covered with a dressing that protects it from the external environment. During this time, no ointments are applied to this area. After suture removal, the scar should only be moisturized, e.g., with baby oil. After about 7-14 days of moisturizing, when there are no more scabs along the healed wound, silicone patches can be applied to the scar. Silicone patches additionally require the use of special compression garments (after breast operations, these are special bras; after abdominoplasty, corsets). In places where it is difficult to use a compression garment, a silicone patch can be replaced with a silicone ointment. The purpose of using the patch is to relieve tension on the scar line and limit the tensile forces affecting the remodeling processes within the scar. Additionally, the patch provides chronic pressure on the scar and protects it from drying out. Chronic use of patches and compression is a proven method that favorably influences a maturing scar. During scar maturation, follow-up examinations with the operating surgeon are recommended. The surgeon assesses whether the condition of the maturing scar is adequate for the time elapsed since wound healing. In case of hypertrophic scar characteristics, ointments with onion extract, e.g., Cepan, ContracTubex, can be used. These ointments have beneficial effects, but only in the case of hypertrophic scars. They should not be routinely applied to every scar. In exceptional situations, collagen production processes in the scar can be reduced by injecting it with steroid medications.

Depending on the above factors affecting wound healing, the following types of scars are formed: 1) Ideal scar; 2) Atrophic scar; 3) Hypertrophic scar; 4) Scar contracture; 5) Keloid (also known as keloid);

A scar will always form at the site of skin discontinuity as a result of healing. It is important that it has the characteristics of an ideal scar. The features of such a scar are: linear character, structure and color resembling surrounding tissues (it is soft, elastic, pale), level with the surrounding skin (it is neither sunken nor raised), no discomfort from the scar. A wound inflicted by a plastic surgeon's scalpel usually heals with an ideal scar. An accidental traumatic wound, even if surgically treated, often heals with an unfavorable scar.

An atrophic scar is characterized by a small amount of scar tissue, which causes it to be sunken relative to the surface of the surrounding skin. It is wide and covered with delicate, parchment-like epidermis with low resistance to injury. It usually represents the regression of a hypertrophic scar that resulted from an injury with tissue loss and healing by granulation (e.g., after a burn) or in people with impaired wound healing.

A hypertrophic scar is a cosmetic problem, but it can also cause scar contracture, thus additionally posing a functional problem. Hypertrophic scars result from healing by granulation, from complications in wound healing, or when the wound crosses the flexion creases of joints. A hypertrophic scar has an uneven surface, is raised above the surrounding skin, hard, and red. Sometimes it causes discomfort (itching, burning). After several to a dozen months, as a result of the maturation process, such a scar spontaneously softens, evens out its surface, and becomes similar to the surrounding tissues. The maturation process proceeds at different rates in different people (individual variability). Scar maturation is accelerated by: 1) Chronic pressure; 2) Massage; 3) Moisturizing; 4) Corticosteroids in the form of injections into the scar; 5) Onion extract ointment – rubbing into the scar for several weeks; 6) Silicone patches and ointments; 7) X-ray irradiation was once used for hypertrophic scars. This method has now been abandoned due to dangerous complications.

Scar contracture is the displacement of tissues by a scar into an abnormal position or the fixation of mobile body parts in an unnatural position. An example of scar contracture with tissue displacement into an abnormal position can be scar contracture of the female breast. A small girl suffers a thermal injury in the area of one breast. A planar scar forms there. During puberty, the hard scar tissue restricts breast development. The breast at the scar site is smaller, and sometimes even deformed. An example of scar contracture of mobile body parts is scar contracture of the elbow, knee, or neck. A scar located on the flexor side of a joint is hard and not very elastic. It does not allow for complete extension of the joint. Surgical intervention for scar contracture is performed no earlier than 6 months after the primary wound has healed. Exceptions are scar contractures with significant functional impairment, e.g., eyelid ectropion with corneal exposure or lip ectropion with saliva leakage from the oral cavity. In these cases, scar correction is performed early. Surgical treatment of scar contracture involves incising the scar (sometimes excising it), repositioning the tissues to their natural position, and covering the defect with a free skin graft or a flap of healthy tissues.

A hypertrophic scar is not the same as a keloid. The diagnosis of a keloid is based on three characteristics. Its extent exceeds the boundary of the primary wound (a hypertrophic scar does not extend beyond the primary wound). A keloid does not undergo a maturation process (it does not decrease in size over time). A hypertrophic scar matures over time, undergoes remodeling, and after 6-12 months changes into an atrophic scar. A keloid always recurs after simple excision. A hypertrophic scar does not recur if, after its excision, the wound heals without complications and the directions of tension in the newly formed wound are changed. There are also other characteristics of a keloid, which, however, are not essential for its diagnosis. Keloids develop „late,” after 3 months from the formation of the primary wound, and can even form several years after the injury. Until then, there is a normal scar at the site of the healed wound. A hypertrophic scar develops 3-4 weeks after the procedure. Symptoms such as spontaneous itching, burning, and even pain, as well as tenderness, i.e., hyperesthesia to minor stimuli, are significantly more severe in keloids than in hypertrophic scars. Keloids are located in specific areas of the body, namely around the sternum, in the deltoid region, on the nape of the neck, and on the earlobes. Hypertrophic scars are usually located on the flexor side of the limbs and tend to form scar contractures. The cause of keloid formation is unknown. A familial and racial predisposition can be observed. Keloids and hypertrophic scars statistically occur more frequently in dark-skinned people, those with blood group A, and allergy sufferers.

Hypertrophic scars result from complications in wound healing (infection, hematoma) or from increased tension in the wound (e.g., crossing flexion creases on the limbs). The formation of keloids and hypertrophic scars affects only humans. There is no animal experimental model for this pathology, which makes scientific research to explain the mechanisms of keloid formation difficult. Generally speaking, hypertrophic scars and keloids result from an imbalance between collagen production and breakdown in the healing wound. These imbalances, favoring collagen production, are significantly more pronounced in keloids.

Treatment:

In the case of an ideal scar, no treatment should be applied. A scar cannot be removed. Where there is a scar, there will always be a scar, so an ideal scar cannot be changed into an even more ideal scar. Sometimes such a scar must be accepted.

Treatment depends on the type and nature of the scar, as well as the time elapsed since the wound healed. Surgical scar correction is not applied within one year of wound healing. During this time, conservative and minimally invasive methods are used to accelerate scar maturation (moisturizing, massage, chronic pressure, onion extract ointments, silicone ointments and patches, steroid injections, lasers, dermabrasion). It should be emphasized that a scar cannot be completely removed. One can only replace one scar with another that is aesthetically and functionally better. The goal of treatment is to achieve a scar similar to an ideal one. Before starting treatment, a diagnosis must be made. The diagnosis of „hypertrophic scar” or „keloid” can only be made based on a well-collected history and observation (subsequent follow-up examinations). Different treatment applies to hypertrophic scars and keloids. It should also be remembered that the skin can be a site for the development of malignant fibrous tumors, e.g., dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. In case of any suspicion of neoplastic growth, a biopsy and histopathological examination (under a microscope) of the tissue taken for examination are mandatory.

Before starting treatment, it is necessary to carefully assess what bothers the patient? Is it scar-related discomfort (itching, pain, tenderness), aesthetic appearance, or functional impairment?

A special case is patients presenting with self-harm scars. These scars are usually located on the skin of the forearm, run transversely to the long axis of the limb, and are numerous. Self-harm occurs during adolescence or early youth, often under the influence of alcohol, peer pressure, or excessive, uncontrolled emotions. In adult life, these scars serve as a shameful reminder of a difficult past. Surgical treatment of such scars involves converting transverse scars into a single longitudinal one. The new scar looks like a post-operative scar, thus not revealing self-harm.

Facial scars with an unfavorable course, crossing lines of reduced tension and natural furrows, constitute a significant aesthetic defect. Correction of such scars involves converting them into others whose direction is similar to natural furrows and lines of reduced tension on the face. This is possible thanks to the so-called Z-plasty or multiple W-plasty. The procedure can be performed no earlier than 1 year after the final healing of the wound that caused the scar. In children, correction can be postponed until after adolescence.

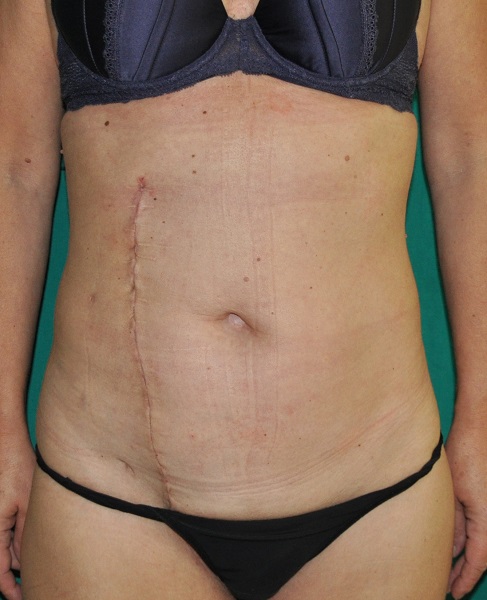

Wide, depressed scars in various areas of the body (e.g., after appendectomy, after C-section) can be transformed into scars closer to ideal using appropriate local plastic surgeries. An important element of the procedure is layered suturing of new wounds. The greatest tension should be distributed among the internal sutures. Skin sutures are only intended for good adaptation of the wound edges.

Surgical treatment of scar contracture involves excising or incising the scar, releasing the contracture, and covering the defect with a free skin graft or a flap of healthy tissues. An inseparable element of scar contracture treatment is postoperative rehabilitation.

The most difficult is the treatment of keloids. The best results are achieved by combining various methods. The use of a single method is almost always associated with keloid recurrence. Treatment begins with minimally invasive methods (chronic compression, massage, steroid injections). Surgical excision of the keloid is a last resort. It should be combined with covering the defect with a skin graft, and even with irradiation of the graft with X-rays.

The sooner after wound healing the process aimed at achieving an ideal scar begins, the better. Fresh hypertrophic scars and keloids respond better to treatment than old scars.

Surgical scar treatment (surgical scar correction) is associated with unavoidable consequences and the risk of complications.

Unavoidable consequences include: 1. General pain and suffering associated with the operation; 2. Swelling of the operated area; 3. Bruising in the operated area; 4. Transient sensory disturbances of the skin in the operated area; 5. A permanent scar always remains at the site of scar correction (different, by design closer to an ideal scar);

Complications: 1. Hematoma in the wound – requires puncture or drainage; 2. Wound infection – requires drainage, antibiotic therapy, may negate the outcome of the operation; 3. Lack of improvement after the procedure; 4. Dissatisfaction with the outcome of the operation;

Recommendations after surgical scar correction are highly individual depending on the body area where the scar is corrected. Common recommendations (regardless of scar location): 1. Immobilization of the operated area (several – a dozen days); 2. Follow-up examinations and suture removal at the time designated by the doctor; 3. Care for the new scar according to the doctor's recommendations.

Photo gallery

Detailed information

In humans, wounds heal by repair, i.e., with the formation of a scar. A scar is fibrous connective tissue that ensures the anatomical continuity of the healing organ or tissue. A scar does not perform the function of the healing organ. A wound can affect the skin and any other human organ or tissue.

Skin heals with scar formation after injury. Every person has some scar on their body from an accidental cut or vaccination. Sometimes we have postoperative scars. However, it sometimes happens that a scar constitutes a significant aesthetic, or even functional, problem and affects a person's entire life.

A scar at the site of a healed wound should perform its function well, meaning it should strongly join the edges of the damaged organ and not impair its function. A scar has a different structure than the surrounding skin. It is harder, stiffer, and has less elasticity and stretchability. The goal of wound treatment is also to achieve a good aesthetic result, so that the scar is barely visible.

Wound healing and the type of scar that will form depend on many factors.

In older people over 65, wounds heal worse than in younger people. The wound achieves sufficient tensile strength after a longer time. This is due to lower collagen production. The connective tissue reaction in the wound is smaller compared to children. Less intense wound healing processes in older people also have their advantages, namely that the scars formed as a result of healing quickly become less visible. In young people, hypertrophic scars with a significant connective tissue reaction are more frequently observed.

The location of the primary wound also influences the intensity of healing processes. Hypertrophic scars and keloids more often form in the sternal area, deltoid region, and on the nape of the neck. In these areas, the skin is very tense. Hypertrophic scars and keloids almost never form on the eyelids and external genitalia. In these areas, the skin is loose and very weakly tensed. Lines of reduced tension are well-expressed there, along which surgical incisions should be made.

The direction of the wound's course in relation to Langer's lines of skin tension is of great importance for the appearance of the scar. Scars located along Langer's lines are narrow, while those running across them are wide. Knowledge of Langer's lines on the human body allows a plastic surgeon to consciously direct their incisions.

The appearance of a scar depends on the method of wound healing. Wounds heal by primary intention or by granulation. Incised wounds that have been surgically closed (wound edges are approximated with sutures after debridement) heal by primary intention. Wounds with tissue loss heal by granulation. In the case of primary intention, all healing processes occur, but they are significantly less intense. The resulting scar is linear and barely visible. In the process of healing by granulation, the processes of collagen production, epidermal coverage of the wound, and scar contraction last long and are significantly more intense. The resulting scar is hypertrophic, and often even causes scar contracture. The aesthetic outcome of healing by granulation is poor.

Complications in wound healing (infection, hematoma, wound dehiscence) affect the final appearance and function of the scar. Complications often lead to the formation of hypertrophic scars.

Genetic predispositions also influence healing processes. Black people and albinos have a greater tendency to form keloids (interesting fact – it sometimes happens that an individual's predisposition to keloid formation is periodic).

The shape of the primary wound influences the appearance and function of the final scar – circular scars tend to contract concentrically and elevate tissues above the level of the surrounding skin.

The appearance and function of a scar depend on the time elapsed since the injury. A scar achieves its final appearance only one year after the wound has healed. Immediately after wound healing, the scar is red, hard, often elevated above the surrounding skin. Over time, the scar softens, fades, and becomes level with the surrounding skin.

Depending on the above factors affecting wound healing, the following types of scars are formed: 1) Ideal scar; 2) Atrophic scar; 3) Hypertrophic scar; 4) Scar contracture; 5) Keloid (also known as keloid);

A scar will always form at the site of skin discontinuity as a result of healing. It is important that it has the characteristics of an ideal scar. Features of such a scar are: linear character, structure and color resembling surrounding tissues, level with the surrounding skin, absence of symptoms from the scar. A wound inflicted by a plastic surgeon's scalpel usually heals with an ideal scar. An accidental traumatic wound, even if treated surgically, often heals with an unfavorable scar.

An atrophic scar is characterized by a small amount of scar tissue, which causes it to be sunken relative to the surface of the surrounding skin. It is wide and covered with delicate, parchment-like epidermis with low resistance to injury. It usually represents the regression of a hypertrophic scar that resulted from an injury with tissue loss and healing by granulation (e.g., after a burn) or in people with impaired wound healing.

A hypertrophic scar is a cosmetic problem, but it can also cause scar contracture, thus additionally posing a functional problem. Hypertrophic scars result from healing by granulation, from complications in wound healing, or when the wound crosses the flexion creases of joints. A hypertrophic scar has an uneven surface, is raised above the surrounding skin, hard, and red. Sometimes it causes discomfort (itching, burning). After several to a dozen months, as a result of the maturation process, such a scar spontaneously softens, evens out its surface, and becomes similar to the surrounding tissues. The maturation process proceeds at different rates in different people (individual variability). Scar maturation is accelerated by: 1) Chronic pressure; 2) Massage; 3) Moisturizing; 4) Corticosteroids in the form of injections into the scar; 5) Onion extract ointment – rubbing into the scar for several weeks; 6) Silicone patches and ointments; 7) X-ray irradiation was once used for hypertrophic scars. This method has now been abandoned due to dangerous complications.

Scar contracture is the displacement of tissues by a scar into an abnormal position or the fixation of mobile body parts in an unnatural position. An example of scar contracture with tissue displacement into an abnormal position can be scar contracture of the female breast. A small girl suffers a thermal injury in the area of one breast. A planar scar forms there. During puberty, the hard scar tissue restricts breast development. The breast at the scar site is smaller, and sometimes even deformed. An example of scar contracture of mobile body parts is scar contracture of the elbow, knee, or neck. A scar located on the flexor side of a joint is hard and not very elastic. It does not allow for complete extension of the joint. Surgical intervention for scar contracture is performed no earlier than 6 months after the primary wound has healed. Exceptions are scar contractures with significant functional impairment, e.g., eyelid ectropion with corneal exposure or lip ectropion with saliva leakage from the oral cavity. In these cases, scar correction is performed early. Surgical treatment of scar contracture involves incising the scar (sometimes excising it), repositioning the tissues to their natural position, and covering the defect with a free skin graft or a flap of healthy tissues.

A hypertrophic scar is not the same as a keloid. The diagnosis of a keloid is based on three characteristics. Its extent exceeds the boundary of the primary wound (a hypertrophic scar does not extend beyond the primary wound). A keloid does not undergo a maturation process (it does not decrease in size over time). A hypertrophic scar matures over time, undergoes remodeling, and after 6-12 months changes into an atrophic scar. A keloid always recurs after simple excision. A hypertrophic scar does not recur if, after its excision, the wound heals without complications and the directions of tension in the newly formed wound are changed. There are also other characteristics of a keloid, which, however, are not essential for its diagnosis. Keloids develop „late,” after 3 months from the formation of the primary wound, and can even form several years after the injury. Until then, there is a normal scar at the site of the healed wound. A hypertrophic scar develops 3-4 weeks after the procedure. Symptoms such as spontaneous itching, burning, and even pain, as well as tenderness, i.e., hyperesthesia to minor stimuli, are significantly more severe in keloids than in hypertrophic scars. Keloids are located in specific areas of the body, namely around the sternum, in the deltoid region, on the nape of the neck, and on the earlobes. Hypertrophic scars are usually located on the flexor side of the limbs and tend to form scar contractures. The cause of keloid formation is unknown. A familial and racial predisposition can be observed. Keloids and hypertrophic scars statistically occur more frequently in dark-skinned people, those with blood group A, and allergy sufferers.

Hypertrophic scars result from complications in wound healing (infection, hematoma) or from increased tension in the wound (e.g., crossing flexion creases on the limbs). The formation of keloids and hypertrophic scars affects only humans. There is no animal experimental model for this pathology, which makes scientific research to explain the mechanisms of keloid formation difficult. Generally speaking, hypertrophic scars and keloids result from an imbalance between collagen production and breakdown in the healing wound. These imbalances, favoring collagen production, are significantly more pronounced in keloids.

Treatment:

Treatment depends on the type and character of the scar and the time that has passed since the wound healed. Surgical scar correction is not used for up to one year after the wound has healed. During this time, conservative and minimally invasive methods are used to accelerate scar maturation (lubrication, massage, chronic pressure, onion extract ointments, silicone ointments and patches, steroid injections, lasers, dermabrasion). It should be emphasized that a scar cannot be completely removed. One can only replace one scar with another that is aesthetically and functionally better. The goal of treatment is to obtain a scar close to ideal. Before starting treatment, a diagnosis must be made. The diagnosis of „hypertrophic scar” or „keloid” can only be made based on a well-collected history and observation (subsequent follow-up examinations). Different treatment applies to hypertrophic scars and different to keloids. It should also be remembered that the skin can be a site for the development of fibrous malignant tumors, e.g. dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. In case of any suspicion of neoplastic growth, a biopsy and histopathological examination (under a microscope) of the tissue taken for examination are mandatory.

Before starting treatment, it is necessary to carefully assess what bothers the patient? Is it scar-related discomfort (itching, pain, tenderness), aesthetic appearance, or functional impairment?

A special case is patients presenting with self-harm scars. These scars are usually located on the skin of the forearm, run transversely to the long axis of the limb, and are numerous. Self-harm occurs during adolescence or early youth, often under the influence of alcohol, peer pressure, or excessive, uncontrolled emotions. In adult life, these scars serve as a shameful reminder of a difficult past. Surgical treatment of such scars involves converting transverse scars into a single longitudinal one. The new scar looks like a post-operative scar, thus not revealing self-harm.

Facial scars with an unfavorable course, crossing lines of reduced tension and natural furrows, constitute a significant aesthetic defect. Correction of such scars involves converting them into others whose direction is similar to natural furrows and lines of reduced tension on the face. This is possible thanks to the so-called Z-plasty or multiple W-plasty. The procedure can be performed no earlier than 1 year after the final healing of the wound that caused the scar. In children, correction can be postponed until after adolescence.

Wide, depressed scars in various areas of the body (e.g., after appendectomy, after C-section) can be transformed into scars closer to ideal using appropriate local plastic surgeries. An important element of the procedure is layered suturing of new wounds. The greatest tension should be distributed among the internal sutures. Skin sutures are only intended for good adaptation of the wound edges.

Surgical treatment of scar contracture involves excising or incising the scar, releasing the contracture, and covering the defect with a free skin graft or a flap of healthy tissues. An inseparable element of scar contracture treatment is postoperative rehabilitation.

The most difficult is the treatment of keloids. The best results are achieved by combining various methods. The use of a single method is almost always associated with keloid recurrence. Treatment begins with minimally invasive methods (chronic compression, massage, steroid injections). Surgical excision of the keloid is a last resort. It should be combined with covering the defect with a skin graft, and even with irradiation of the graft with X-rays.

The sooner after wound healing the process aimed at achieving an ideal scar begins, the better. Fresh hypertrophic scars and keloids respond better to treatment than old scars.

Surgical scar treatment (surgical scar correction) is associated with unavoidable consequences and the risk of complications.

Unavoidable consequences include: 1. General pain and suffering associated with the operation; 2. Swelling of the operated area; 3. Bruising in the operated area; 4. Transient sensory disturbances of the skin in the operated area; 5. A permanent scar always remains at the site of scar correction (a different one, by definition closer to an ideal scar);

Complications: 1. Hematoma in the wound – requires puncture or drainage; 2. Wound infection – requires drainage, antibiotic therapy, may negate the outcome of the operation; 3. Lack of improvement after the procedure; 4. Dissatisfaction with the outcome of the operation;

Recommendations after surgical scar correction are highly individual depending on the body area where the scar is corrected. Common recommendations (regardless of scar location): 1. Immobilization of the operated area (several to a dozen days); 2. Follow-up examinations and suture removal at the time designated by the doctor; 3. Caring for the new scar according to the doctor's recommendations;

Characteristics of an ideal scar

A scar should be:

- Narrow

- Level with the surrounding skin

- Soft

- Movable relative to the underlying tissue

- Pale

- Without symptoms (itching, pain)